EMNLP 2025 in Suzhou

EMNLP 2025 in Suzhou

Disclaimer: The research discussed in this post is entirely unrelated to my professional responsibilities. The work described here reflects independent academic activity that I pursue out of personal interest in modern machine learning research. All papers referenced below have been officially approved for publication and contain no proprietary or confidential information from my current employer. The material presented should not be interpreted as investment advice, financial analysis, or as having any applicability to my employer’s activities. Its relevance is strictly limited to the advancement of empirical methods and scientific understanding in machine learning.

Motivation

This year at EMNLP 2025 in Suzhou, my colleague Khaled Al Nuaimi and I attended the conference so that Khaled could present his paper on Evasive Answers in Financial Q&A, and also to explore current R&D trends in empirical NLP.

While walking through the poster sessions, we saw a dozen of papers closely related with our recent contributions and joint research program with Khalifa University, where I co-supervise the PhD work of my colleagues:

Across these doctoral projects, we are building a coherent, multi-layer research program at the intersection of:

- Complex networks & complexity science (financial labour networks, institutional networks, contagion processes)

- Feature importance & explainable AI (alignment between model predictions and explanations in LLMs & Graphs (Networks) ML models)

- Multimodality: audio + text (tone, prosody, evasiveness, spoken Q&A behaviour)

- Financial Q&A and behavioural analytics (linguistic deception, psychological discourse strategies, managerial behaviour)

- Agent-based modelling (ABM) with explainable agents (replacing zero-intelligence coin-flipping agents with more realistic, behaviourally grounded AI agents)

At EMNLP 2025, we encountered many papers that map surprisingly well onto this agenda, in some cases reinforcing our assumptions, in others providing tools or methodologies we can directly adopt.

Below is a curated summary of the key papers we saw and how they connect to our ongoing work.

Relevant (to us) EMNLP 2025 Papers

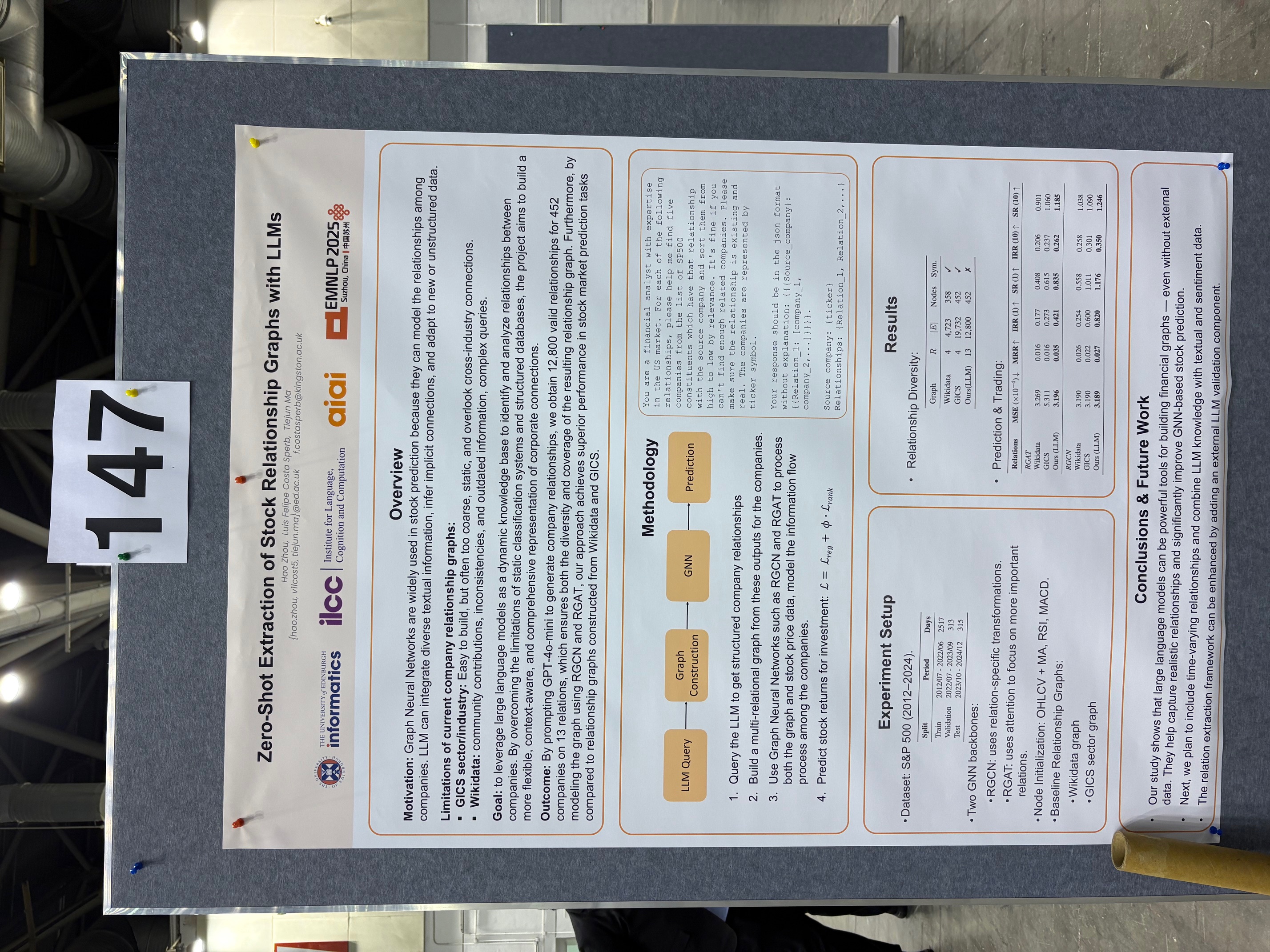

Zero-Shot Extraction of Stock Relationship Graphs with LLMs (Zhou et al., FinNLP 2025)

What the paper does:

- Uses LLMs as zero-shot knowledge bases to extract rich, typed company–company relations (supplier, competitor, JV partner, investor…).

- Builds multi-relational stock-market graphs from LLM outputs.

- Trains GNNs (RGCN, RGAT) for stock return ranking, outperforming GICS/Wikidata graphs.

Connections to our research:

This work aligns most closely with Abdulla’s line of research. Beyond reconstructing networks of past co-employment directly from SFC data, we could extend the financial ecosystem by using LLMs to infer missing inter-institution relationships. For example: competition, parent–subsidiary structures, shared ownership, or other strategic ties.

Adding these extra edges would enrich Abdulla’s labour-contagion models by capturing sub-industry exposure, competitive pressures, organizational linkages, and cross-firm risk propagation. In short, it gives us a more complete picture of how information, shocks, or turnover might spread across the ecosystem.

From the perspective of our agent-based modelling (ABM) vision, a multi-relational LLM-inferred graph provides a richer structural layer for agents to operate on. Employee-agents could factor in market competition or firm relations when deciding whether to move to a new opportunity, while firm-agents could incorporate similar relational cues when adjusting headcount or assessing talent flows. This creates a more behaviourally realistic and environmentally aware agent society than classic zero-intelligence ABMs.

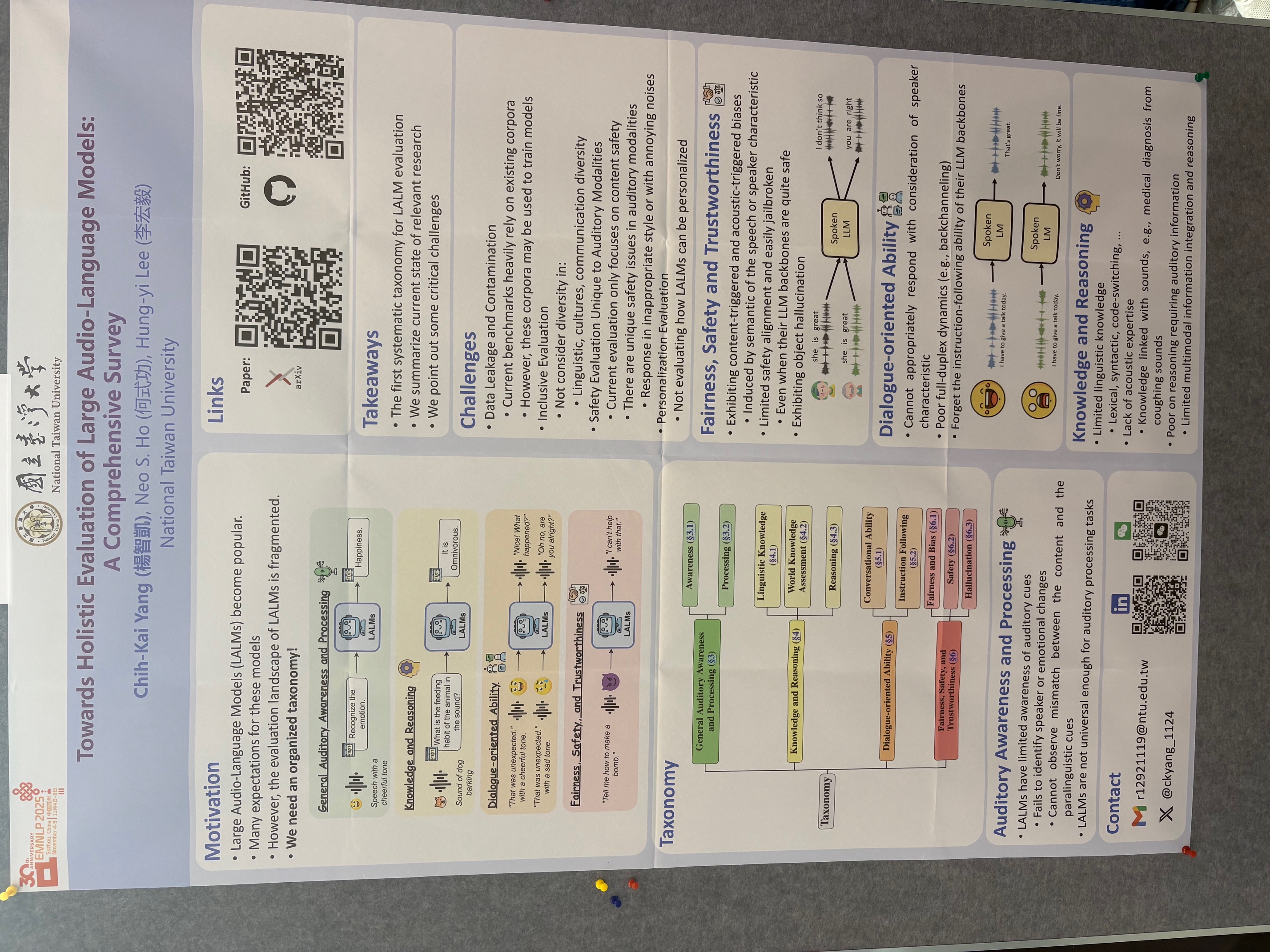

Towards Holistic Evaluation of Large Audio-Language Models: A Comprehensive Survey (Chih-Kai Yang et al.)

What the paper does:

A taxonomy for evaluating audio-language models (LALMs), organized along four axes:

- Auditory awareness & processing

- Knowledge & reasoning

- Dialogue-oriented ability

- Fairness, safety & trustworthiness

It also highlights several gaps in current audio-NLP practice:

- No clean separation between content and paralinguistic cues

- Weak robustness evaluation (noise, speaker variation, accents)

- Limited cultural/linguistic diversity in benchmarks

- Limited evaluation of dialogue quality and response appropriateness

Connections to our research:

Hamdan’s first research contribution: Residual Speech Embeddings

A natural question is: What differentiates LLMs from LALMs? In principle, LALMs should integrate auditory information in addition to text: capturing tone, speaker traits, emotional signals, and other paralinguistic cues that are lost in transcripts.

However, the survey highlights a consistent limitation: current LALMs exhibit very limited auditory awareness. They often fail to detect speaker changes, emotional shifts, or mismatches between lexical content and paralinguistic delivery. In practice, their behaviour is much closer to text-only LLMs than to genuine audio-language models.

These observations align closely with what we have seen empirically. This is precisely the motivation for Hamdan’s work on Residual Speech Embeddings, where we demonstrate that self-supervised speech models tend to over-emphasize lexical information at the expense of paralinguistic cues.

Our approach explicitly removes the lexical component from the speech embedding space, leaving a representation that captures tone and other non-textual characteristics. Empirically, we show that this improves performance on tone-classification tasks, confirming that isolating the paralinguistic signal is beneficial.

For reference:

This EMNLP paper essentially validates the direction of our work: the field currently lacks benchmarks that disentangle content from paralinguistic cues, and residual speech embeddings provide a practical step toward filling that gap.

It is also worth noting that Hamdan’s work naturally connects to Khaled’s research on financial Q&A. One of Khaled’s recent contributions focuses on detecting evasive answers in earnings calls and FOMC press conferences, based purely on the textual transcripts. A logical next step is to extend this analysis to the audio recordings themselves.

Working directly from audio opens new questions that transcripts cannot capture:

- Are there identifiable paralinguistic cues associated with evasive answers?

- Do these cues vary depending on the type of evasive tactic employed?

Hamdan’s residual embeddings provide exactly the kind of representation needed to explore these audio dimensions of evasiveness in a controlled and interpretable way.

From a broader perspective, this line of work also hints at a longer-term, more speculative direction for our agent-based modelling (ABM) research. If we can reliably disentangle and quantify paralinguistic cues, it becomes conceivable—though certainly not immediate—to develop speech-enabled agents whose behaviour is influenced by vocal signals such as stress, confidence, or hesitation. While this is not a short-term objective, it illustrates how multimodal modelling could eventually lead to more realistic simulations of financial decision-making dynamics.

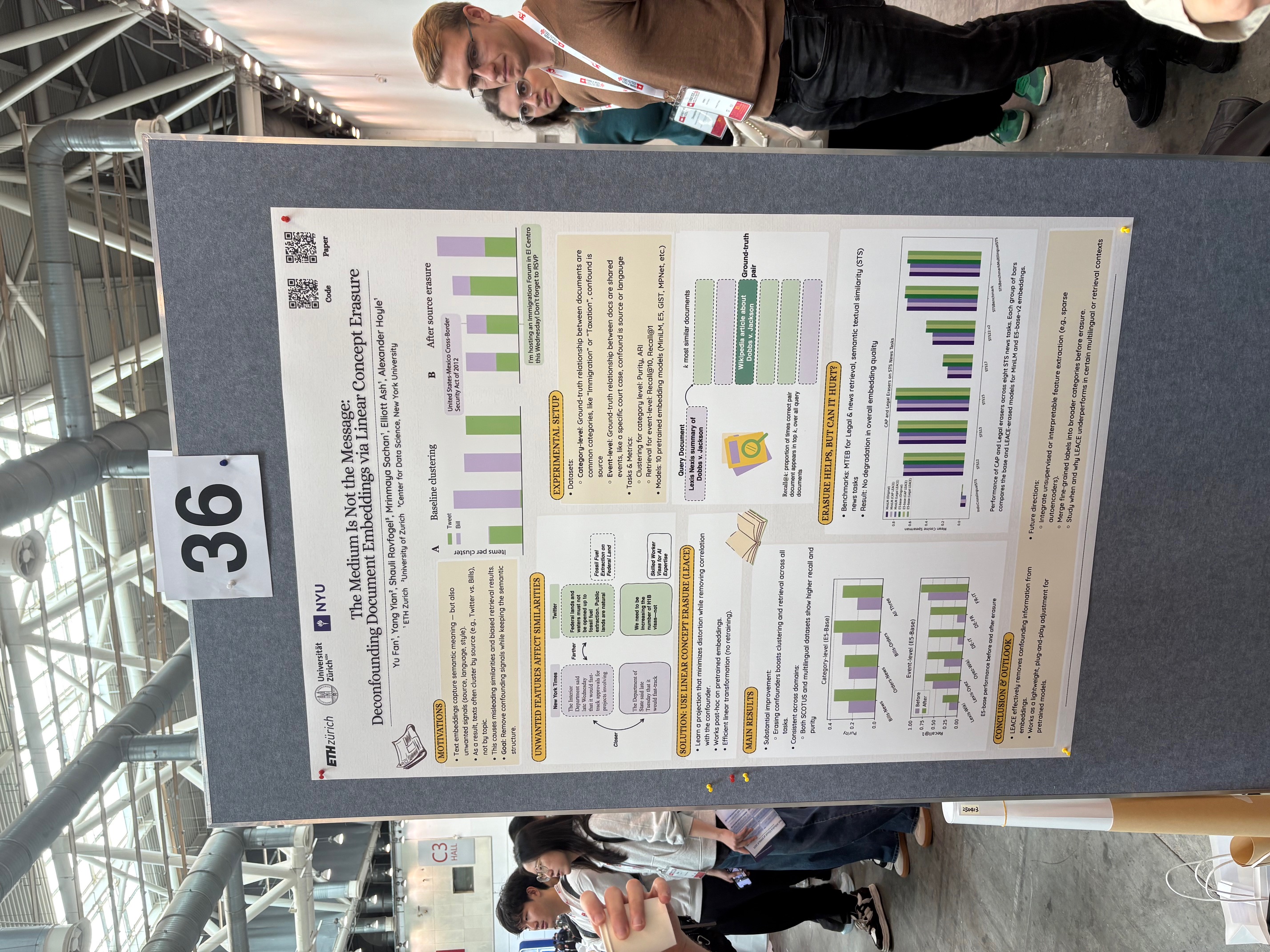

The Medium Is Not the Message: Deconfounding Document Embeddings via Linear Concept Erasure (Fan et al.)

What the paper does:

Embedding-based similarity metrics between text sequences can be influenced not just by the content dimensions we most care about, but can also be biased by spurious attributes like the text’s source or language. These document confounders cause problems for many applications, but especially those that need to pool texts from different corpora.

To mitigate this, the authors introduce Linear Concept Erasure (LCE), a linear projection method that identifies the subspace corresponding to these confounders and removes it, while preserving the semantic core of the representation. Their main findings are:

- cross-corpus clustering and retrieval improve after removing the confounder subspace;

- downstream semantic tasks remain essentially unchanged, which is the expected outcome (semantics are preserved, and only nuisance variation is removed);

- the method is simple and computationally light.

In practice, this is a form of representation surgery: identify the part of the embedding space capturing the unwanted factor, project it out, and keep the rest.

Connections to our research:

This paper reinforces an intuition that also underpins Hamdan’s work on Residual Speech Embeddings: To clean the representation space by removing unwanted components.

There is a clear structural similarity between the two approaches:

- Residual speech embeddings remove the linear component of speech that can be predicted from text, isolating paralinguistic information;

- LCE removes the linear component of text embeddings that corresponds to medium/domain/style, isolating semantic information.

In both cases, the idea is the same:

Identify a linear subspace corresponding to an unwanted factor, remove it, and work with the cleaned embedding.

We used the term residual embedding simply by analogy with “residual returns” in quantitative finance, where regression residuals are often used to remove unwanted exposures. LCE formalizes a closely related idea on the text side, but using discriminative subspace estimation rather than cross-modal regression.

This opens several possibilities relevant to our research program:

- removing speaker identity or channel artifacts from audio embeddings;

- removing demographic confounders in textual or multimodal representations (cf. our name-based demographics study);

- isolating emotional or deceptive cues in financial Q&A;

- making embeddings cross-corpus comparable by suppressing stylistic and format-specific variation across sources like broker reports, earnings calls, and regulatory filings.

Overall, LCE provides an elegant confirmation that linear subspace removal, the core idea behind Hamdan’s residual embeddings, is a powerful and general approach for disentangling competing factors in representation spaces.

Finally, This echoes an intuition I had years ago when doing topic modelling on business descriptions: the dominant axis of variation was almost always the industry sector, which is obvious but not very informative. Removing that first dimension (for example by residualizing to sector embeddings) may be necessary to reveal more interesting structure.

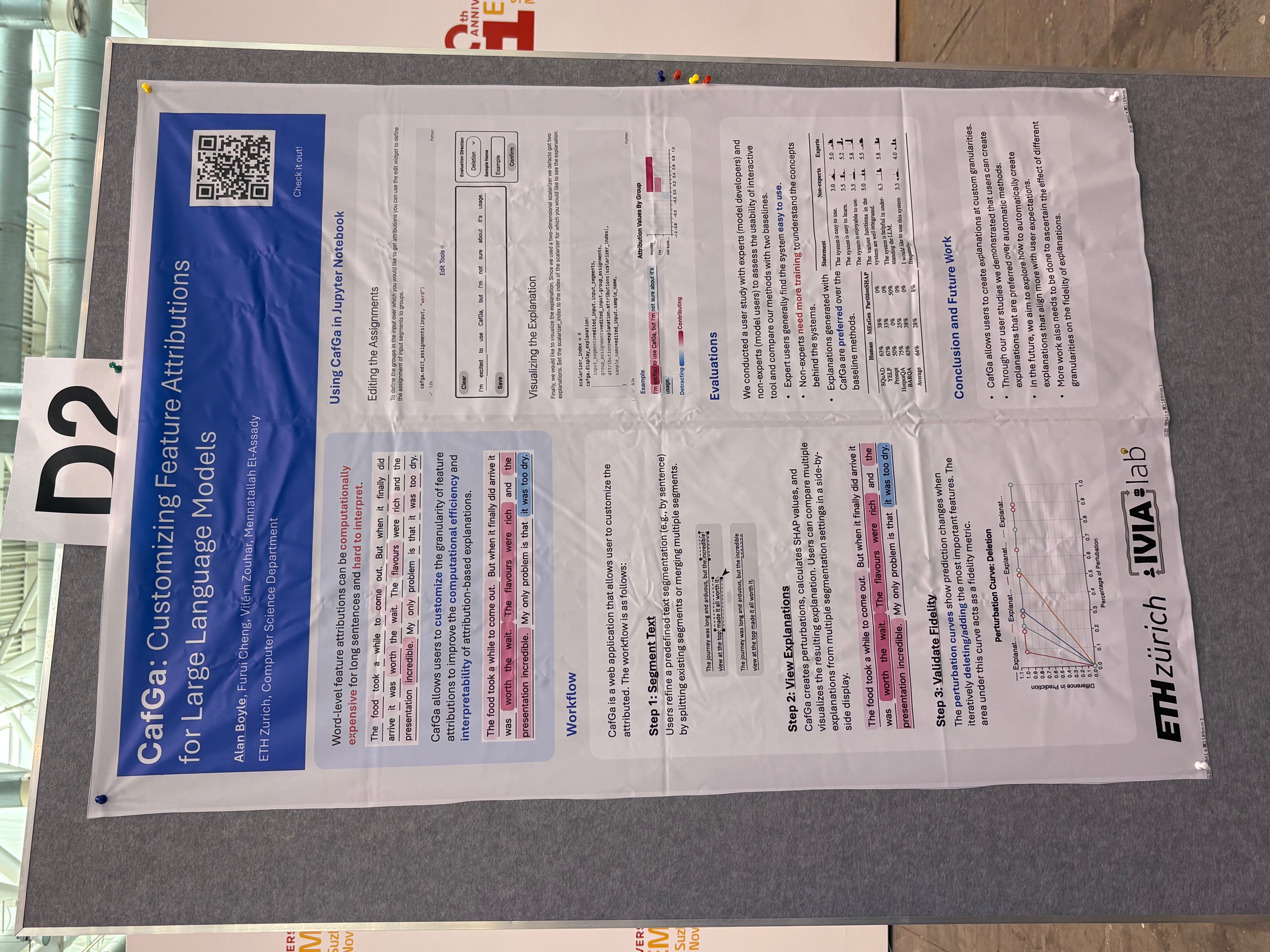

CafGa: Customizing Feature Attributions to Explain Language Models (Boyle et al.)

What the paper does:

CaFGa proposes an attribution framework that lets users control the granularity of explanations for LLM decisions. Instead of relying on token-level heatmaps, typically noisy, unstable, and expensive, CaFGa groups text into interpretable segments (sentences, clauses, rhetorical units) and computes attributions at this coarser, more meaningful level.

A key component is the use of perturbation–fidelity curves to assess whether the explanation is faithful to the model’s actual decision process. The idea is simple: remove or mask the high-attribution segments and measure how the prediction changes. Faithful explanations yield steep fidelity curves; unfaithful ones remain flat.

The authors show that coarse-grained explanations tend to be more stable, more readable, and more faithful to model behavior than traditional word-level attributions.

Connections to our research:

Although Saeed’s credit-risk classifier operates on tabular features rather than text, CaFGa suggests a direct methodological analogue: Group features into semantic blocks (employment, income, liabilities, credit history) and compute block-level attributions. Perturbation–fidelity curves would then allow us to test whether the explanation aligns with the model’s true decision boundary. This complements our ongoing work on explanation alignment, where we repeatedly observe that LLM-generated natural-language explanations diverge from the model’s actual reasoning. CaFGa provides a principled way to quantify this divergence.

The paper is also highly relevant to Khaled’s work on evasive answers in financial Q&A. CEO (and CFO/COO) responses in earnings calls naturally decompose into meaningful discourse segments: direct answers, hedges, topic shifts, credibility boosters, vague qualifiers, and so on. CaFGa’s segment-level attribution framework fits this structure almost perfectly. It would allow us to quantify which parts of an answer contribute most to the model’s evasiveness prediction, and whether those attributions are faithful. This could naturally lead to a follow-up study on segment-level explanations for evasive answer detection.

Beyond academic value, such a tool would be practically useful for financial analysts during live Q&A sessions or one-to-one calls with management. Highlighting the segments most responsible for an “evasive” classification, together with an indication of in which direction the answer is evasive (topic shift, hedging, excessive reassurance, lack of specificity), could help analysts decide when to push further, and on which aspect of the response to follow up.

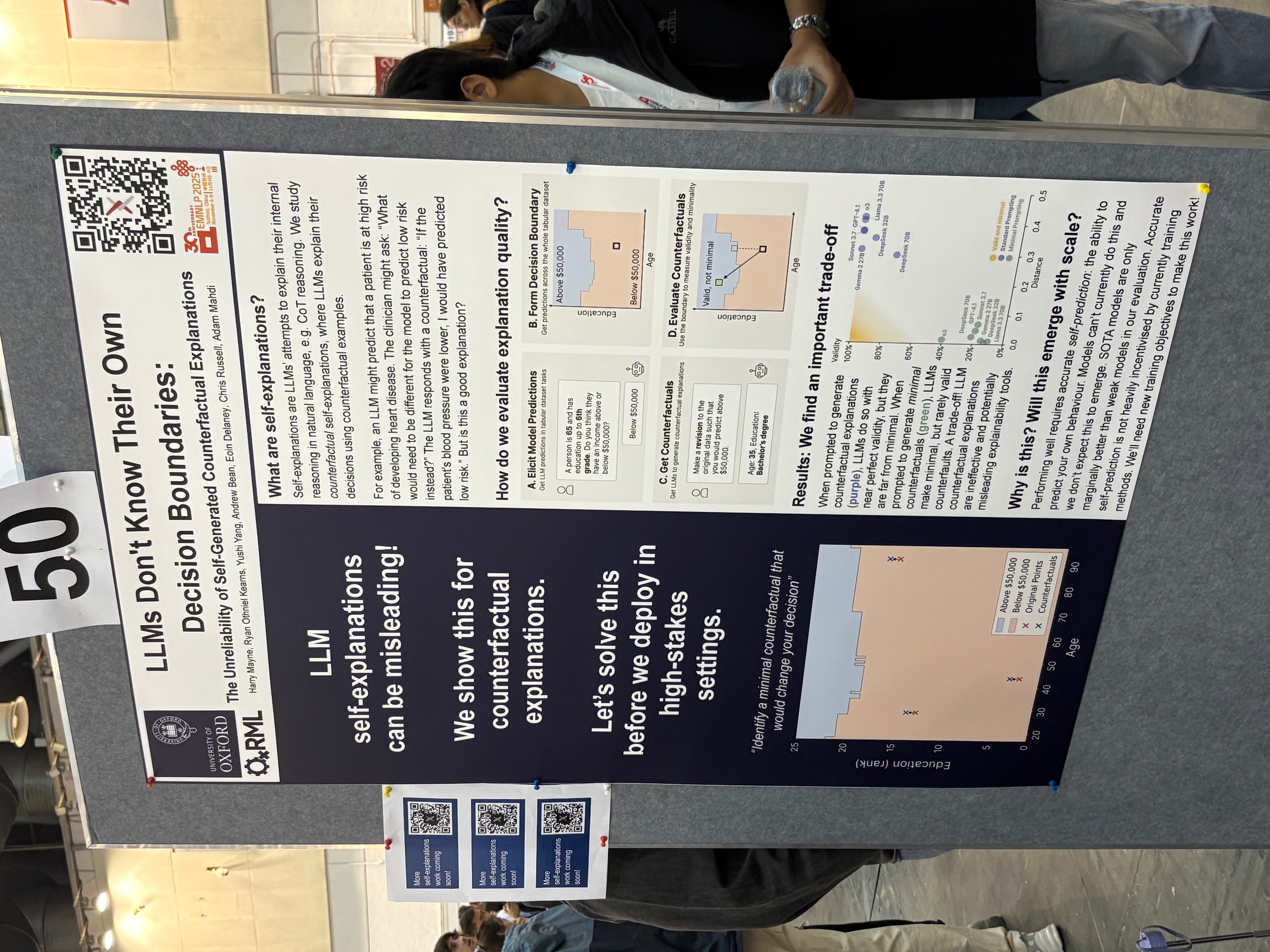

LLMs Don’t Know Their Own Decision Boundaries: The Unreliability of Self-Generated Counterfactual Explanations (Mayne et al.)

What the paper does:

This paper investigates whether LLMs understand their own decision boundaries when used as classifiers. The authors evaluate a simple but revealing setup: small tabular datasets (2–4 features) are converted into natural-language profiles, and the LLM is asked to (i) make a prediction and then (ii) provide a self-generated counterfactual explanation (SCE): “What is the smallest change to this profile that would flip your decision?”

Crucially, authors can enumerate the full input space, so they know exactly where the decision boundary lies.

They evaluate two properties:

- Validity: Does the counterfactual actually flip the model’s prediction?

- Minimality: Is the suggested change close to the true decision boundary?

The core findings:

- When asked for any counterfactual, LLMs often produce valid but highly non-minimal edits (overshooting the boundary).

- When asked for the smallest change, LLMs produce minimal-looking edits that frequently fail to flip the prediction.

- No current model (including GPT-4.1, o3, Claude Sonnet 3.7) achieves both validity and minimality at the same time.

In practice: LLMs generate counterfactuals that sound correct but fail to match the true decision boundary.

Connections to our research:

This paper directly reinforces the findings from Saeed’s paper on credit-risk explanation alignment, where we show that LLM-generated explanations for credit decisions often diverge from the factors that actually drive the model’s classification. That work focused on feature-importance misalignment; this paper adds a complementary phenomenon: boundary-awareness misalignment.

Together these papers paint a consistent picture:

- LLMs struggle to articulate why they made a decision (feature attributions).

- LLMs also struggle to articulate how to change the decision (counterfactuals).

The methodology in this poster offers a clean way to test this in our credit-risk setting:

- Use the same borrower profiles and prompt templates from Saeed’s work.

- Ask the LLM to predict default vs. non-default.

- Request a self-generated counterfactual: “What is the minimal change that would flip your decision?”

- Parse the edited profile back to tabular form.

- Re-query the model and measure validity + minimality.

Can we replicate this research in our setting?

While a direct replication of their protocol in the credit domain is rather straightforward, the more interesting direction for us is constructive: Can we help LLMs generate counterfactuals that are both valid and minimal?

This suggests a methodological extension: Adapting classical ML counterfactual engines (e.g., DiCE) on LightGBM) to identify truly minimal edits… This could lead to a more ambitious follow-up paper: “Teaching (Credit) LLMs Their Own Decision Boundaries” where the goal is not only to expose the misalignment but to improve boundary-awareness using hybrid ML–LLM pipelines (tentatively).

Conclusion

This quick wrap-up covers only a handful of the papers we came across, but they were among the most directly connected to the research lines pursued by the PhD students I’m co-supervising. Each of them sharpens or extends the work we’ve already been doing, whether on representations, audio–text multimodality, explainability, or financial Q&A behaviour.

I’m writing this just a few hours before boarding my flight to NeurIPS (San Diego). With a bit of luck, I’ll come back with another batch of papers that are equally interesting and aligned with our research program.